Update After the Election We Chatted With Cramer Again About Rural Whites Trump and Racism

O ne evening a few summers ago, I walked from my house to the canton fairgrounds. It was a long July solar day, and the sun still hung above the hills that surround the small western Colorado town where I live. People packed the bleachers of an outdoor arena to watch a rodeo.

Shortly earlier the bullriding began, a rodeo clown strolled to the center of the dirt field and began his dark with a joke. Information technology went something similar this:

In that location was a man who died afterwards a good life on globe, and St Peter met him at the pearly gates and welcomed him to Sky. When he got within, the human noticed that there were clocks all over the place, each set to a different time.

"What's with all the clocks?" he asked.

"Those are liars' clocks," St Peter answered. "They keep track of the lies that people tell on earth."

"Whose is that?" the man asked, pointing at a clock set to two.

"That'southward Noah's clock," St. Peter said, "he lived 800 years and only lied twice."

"How virtually that one?" the homo asked, looking at a clock that showed noon.

"That's Mary's clock," St. Peter said. "The Mother of God didn't tell a lie her whole life."

The homo thought for a minute. "How well-nigh Hillary Clinton's clock?" he asked.

"Oh, that'due south in Jesus's office . He uses information technology as a ceiling fan."

This is not a new flake. The same story was told in similar settings about Barack Obama, and a friend who grew up in the area noted that his father's 1990s version had Nib Clinton as the punchline. At the rodeo, there was an assumption shared by clown and oversupply: a Democrat, accept your pick, would be the butt of the joke.

When it comes to rural America, the Democrats are not doing well. They take lost Arkansas, which had two Democratic senators as recently as 2010. They've lost Minnesota'southward subcontract country and its Iron Range in the north – one time strongholds of the state'south Democratic-Farmer-Labor political party. As of 2020, they're on the verge of losing south Texas. And they've lost Colorado's Western Slope. In 2010, the region was held by a Democrat, but information technology'south now represented in Congress by Lauren Boebert, best known for tweeting about the locations of lawmakers during the Jan 6 riot, pledging to carry her handgun into Congress, and going on a racist tirade against Representative Ilhan Omar.

Unlike some of her fellow far-correct House members, Boebert does not represent a deep-red seat. In 2020, she won with only 51.4% of the vote. Colorado's 3rd district is large and varied, covering the state's unabridged western half. Federal public lands comprise much of the area, which likewise includes ski towns high in the Rockies, large chunks of farmland, and a couple of midsize cities. The areas most the New Mexico edge have substantial Latino populations.

This has non inspired Boebert to moderate her positions or reach out to those who didn't vote for her in 2020. On the contrary, she continues to dial up a persona that seems designed to inflame the civilisation wars and offend many of her own constituents. Add together to her political theatrics the fact that she hid a $1m connection between her husband and an oil and gas firm, and it's difficult to think of a better opportunity for Democrats to milkshake their losing streak and regain a rural seat.

The party seemed to agree, and it adopted a well-worn approach. A frontrunner for the Democratic nomination emerged early on in Kerry Donovan, a popular state senator widely viewed as a rising star in Colorado. Her entry into the race received attending from Politico and the Associated Press, and she was boosted by national Autonomous fundraising groups, bringing in nearly $2m by the end of September 2021. Her start entrada ad depicted her on horseback, sporting a cowboy hat. A few seconds later, she lugged hay bales in slow motion, equally if to secure her credentials as a "rancher", a label too affixed to her campaign Twitter account.

Donovan does indeed own a ranch, but in that location's more to the movie. She also lives in the swank ski town of Vail, which was never part of the third commune. On the ranch, which sits some miles w of the boondocks and was included in the third commune's old boundaries, her family raises fuzzy Scottish highland cows. As a local Autonomous official told me when Donovan entered the race: "That's not ranching in western Colorado. That's a hobby." In Nov, Donovan suspended her bid after Colorado's redistricting commission just barely sliced the ranch out of Boebert's district. (Seven other Democrats remain in the primary.)

In recent election cycles, a number of Democratic candidates have adopted tropes of rural authenticity in like style. They appear in entrada ads with rustic farm imagery, a well-placed truck to lean an elbow on, and, of course, cowboy hats. There are often guns involved.

The former Indiana senator Joe Donnelly chopped wood in i entrada ad – he "separate" from the national party, you meet. In 2017, there was Rob Quist, a "singing cowboy" with no prior political experience whom Montana Democrats picked to run for an open up House seat. Quist never appeared in public without a hat, and information technology was a great hat, but he however lost. Last fall, the longtime New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof announced that he was running for governor of Oregon. His Twitter business relationship describes him equally an "Oregon farmer". (In January, country election officials determined that Kristof is ineligible to run for governor, because he does not meet Oregon's residency requirements.)

These put-on personas – cowboy, rancher, farmer – are meant to signal not only authenticity, but as well an independence and toughness tied to the mythos of the borderland.

Of course, Republicans use these tactics every bit well, in a tradition that goes all the fashion back to Teddy Roosevelt. Ronald Reagan transformed his Hollywood cowboy roles into a political persona. He was often photographed in a broad-brimmed hat or on a horse on his California estate. Both Bushes, especially the younger one, cultivated Texan identities with boots, buckles, and pearl snap shirts, symbolism that became essential to selling their wars overseas.

More contempo examples become well-nigh too numerous to count. Consider Donald Trump Jr'due south habit of dressing in camouflage and blaze orangish. On Tucker Carlson's new interview-based show, the anchor appears to broadcast from a log cabin, having traded in his signature preppy, bow-tied look for a flannel shirt.

Some politicians seem not to understand the costumes they wear: Ryan Zinke, Trump'due south kickoff interior secretarial assistant, in one case wore his cowboy hat backwards in a photo op with Mike Pence. He also rigged his fly-rod the incorrect manner around while fishing with a reporter from Outside Magazine. Today, Zinke is favored to win Montana'south new House seat, though according to a deeply reported Politician story, he appears to spend most of his time in Santa Barbara, California.

Americans of all kinds, urban and rural alike, rightfully experience excluded from the centers of political decision-making and ignored by a giant, faceless bureaucratic state.

For a politician, exuding a sense of familiarity, of shared concern and experience with the citizens you hope to represent, can exist a valuable thing – if you can pull it off.

Some tin – take Senator Jon Tester, Montana's sole Democrat holding statewide role. Tester notwithstanding works the dryland wheat farm in the rural Montana county where he was raised. When he was nine years old, he was feeding raw beef into a meat grinder in his family'southward butcher shop when his left paw slipped into the machine. He lost three fingers. A 2022 Washington Mail service contour notes that he still uses the same meat grinder.

Tester can campaign as a farmer without fearing accusations of hypocrisy, and in a state that has gone from royal to deep scarlet in recent elections, he wins consistently. But Tester is the exception that proves the dominion. Finding seven-fingered farmers is not a political strategy, and actualization accurate, whatever that may mean, is no guarantee of smart policy or political courage.

Tester, who has spent the past few years criticizing Democrats for abandoning rural voters, voted to deregulate the fiscal sector in 2018, claiming that the Dodd-Frank legislation passed afterwards the financial crunch had hurt minor community banks. (An Associated Press factcheck found that the laws were not the primary cause of consolidations and closures.)

Some on the left take an caption for this state of diplomacy. Laid out most famously in Thomas Frank's influential What'southward the Thing with Kansas?, and most recently invoked past Bernie Sanders backers who note his popularity in rural areas, the argument goes like this: like the residual of the country, rural communities have been and remain dominated and exploited by the economic forces that transcend local command – deregulation, unrestrained financial markets, and deindustrialization. If Democrats would simply run on bold economic populism, it goes on, rural voters would overlook the cultural issues where they align with Republicans and vote in accordance with their economical interests.

Frank's account of the trouble with Kansas has troubles of its own. His diagnosis of the Democratic party's shortcomings is not wrong, just his remedy is simplistic. It misunderstands how political motivations work at an individual level. Yeah, the economic forces that tear apart rural communities and lives are textile – most things are. These forces that remade and degraded rural economies also deepened course divides, and consolidated wealth in the hands of a few. Only the rural identities and cultural norms that formed in response to these forces are securely held, not hands discarded, and, crucially, not always functionally related to economical atmospheric condition in ways that leftists would prefer. Correct now, rural America's ascendant political civilization is conservative. Any serious effort to build political power here must begin by conceding this fact.

This is a tangle. Republicans pander to rural voters with fabricated authenticity, with simulated displays of rural cred – and win. Democratic attempts at replicating this strategy predictably fall flat. A watered-down version of GOP cultural politics, taken in the context of the party'due south electoral slide in rural areas, smacks of desperation. Some leftists treat rural Americans as possessed by an enchanting ideology, certain to fall into line in one case the spell is broken.

Untying this knot requires an understanding of what's happened to rural America and why the caricatures that both parties rely on float far from the truth, failing to acknowledge its political complication and demographic variety. Virtually a quarter of rural residents are not white, an accelerating trend co-ordinate to the 2022 census. That a majority of Ethnic Americans alive in rural areas – and nigh sovereign tribal land is rural – is often ignored. Lower-income people and the poorest rural Americans tend not to vote at all. And with both parties, each in its own way, taking rural areas for granted, can you lot blame them?

A century agone, there were more 6 million farmers; today, fewer than 750,000 remain. However the US's agricultural output has increased fourfold since then, while total acres farmed have declined only slightly.

Same prepare of resources, more upper-case letter, fewer owners: this is an instructive way of understanding the economic stratification that has occurred in many rural communities. A class of local elites owns the valuable land that surrounds a typical minor town, which is home to a post office, public schools, a grocery store, and sometimes a infirmary.

According to a recent Atlantic article by Patrick Wyman, the owners of physical avails – fast food franchises, apartment complexes, auto dealerships – make up the remainder of this scaled-down bureaucracy. They sit on local non-profit boards, run the sleeping room of commerce, and are influential members of their churches. They often hold elected function. And they frequently vote. Wyman called this class of people the American gentry: local oligarchs, with wealth more often tied up in material assets than hedge funds.

As Wyman explains, the rural gentry lack the familiar emblems of farthermost wealth; these are non people with luxury penthouses, Wall Street offices, wealth accumulated in global finance, and offshore bank accounts. Simply on the basis at the town or regional level, they hold substantial economic power and are disproportionately responsible for the political constitution of rural areas.

Excluded from the gentry are the vast majority of rural Americans. The political messaging of both major parties tends to glorify rural America as full of small farms and yeoman farmers. In reality, American agriculture is enormously reliant on government subsidies and tax breaks, while education, healthcare, manufacturing, and retail employ more rural Americans than agriculture, as of the 2022 census. As for all that farmland – hundreds of millions of acres nationwide – it is increasingly held by the wealthy and powerful.

In early on November, a 127-acre Iowa farm sold at auction for $18,500 per acre. Every bit Mother Jones reported, institutional investors like Prudential, Hancock, and TIAA have purchased huge amounts of farmland in recent years. The unmarried largest possessor of American farmland, though, is Bill Gates, with holdings spread across the country. His plans for the land are non clear, only the fiscal incentives are obvious. With the climate crisis set to dramatically reduce the corporeality of arable land, Gates likely sees this oncoming scarcity equally a smart investment. He's probably right.

Fear of resource consolidation in the hands of the powerful few has been a constant in rural areas since America's founding. In the mid-1830s, the English sociologist Harriet Martineau spent several years traveling around the US and recording her observations of the new land, a pop activity among European intellectuals of the fourth dimension. A characteristic of Americans, in Martineau'due south view, was pride in the country, in its vast stretches and easy availability. (Though a perceptive observer of the U.s.a.'southward slaveholding economy and a supporter of the early abolitionist movement, Martineau failed to mention the removal of Ethnic nations, the genocide that made the land available in the beginning place.)

In her book Club in America, Martineau described a "peachy danger" that Americans seemed on guard against. "They have always had in view the disadvantage of rich men purchasing tracts larger than they could cultivate," she wrote. "They saw … that it is inconsistent with republican modes that overgrown fortunes should arise by ways of an early grasping of large quantities of a cheap kind of belongings."

That attitude did not last. In 1862, the Homestead Act opened hundreds of millions of acres of land to settlement, nigh of information technology in the western US and taken from Ethnic nations by force. The police stipulated that the land be doled out in parcels of upwards to 160 acres, but thanks to loopholes, fraud, and poor enforcement, state speculators and companies were able to obtain much larger tracts on the inexpensive. Cattle barons acquired huge land holdings. Their herds overgrazed the range, and in the course of but a few decades, desert began to replace grassland and enabled the spread of cheatgrass and other invasive species that now fuel the wildfires that flare each summer.

By the late 19th century, erratic article markets were afflicting midwestern grain farmers, while in the south, Black and poor white tenant farmers were trapped in extortionist credit systems, working country they did not own. Agrarian anger fed the populist movements of time, which formed, in role, every bit a response to emerging monopolies in the meatpacking and milk industries. Successive waves of consolidation followed in the 1920s and 1930s, caused by low crop prices and the Great Plains drought that led to the Dust Basin.

All of these issues – market consolidation, farm prices, the price of food for an increasingly urban and unionized workforce – converged in the Roosevelt administration'south response to the Corking Depression. In crafting the New Deal, the administration ultimately prioritized the interests of commercial farmers, subsidizing their incomes while implementing production caps. In the southward, communist and socialist organizers had some success edifice coalitions between poor white and Black farmers, bonded in their resistance to the cotton and tobacco companies that dominated the land.

Only in the end, big business concern won out. Agricultural corporate empires – including some, like Tyson Foods, that persist today – formed, while federal policy bankrupted thousands of small and tenant farmers. Though today the New Bargain is seen equally a height of progressive policymaking, its impact on rural America is mostly ignored. In many ways it was the dawn of modernistic agribusiness, the historian Shane Hamilton writes, which brought with it "the acceptance of a certain degree of monopoly ability within the farm and food economy".

These trends accelerated after the second world state of war, with the advent of industrial farming and its new pesticides, combine harvesters, fertilizers, and seed technologies. Federal agriculture policy facilitated these changes in the course of large subsidies and enormous, publicly funded water infrastructure projects, which fabricated large-calibration irrigation possible in arid regions. In 1973, as global grain prices soared, Richard Nixon's agronomics secretary Earl Butz told farmers to "get big or get out". By the 1980s, commodity prices had declined, endangering the farmers who had taken on debt in social club to go big, as instructed. Drought compounded these difficulties.

At the elevation of the farm crisis, more than 500 farm properties were selling every month at foreclosure auctions. In 1985, a larger number of agricultural banks failed than in any yr since the Great Depression, and by the stop of the decade, hundreds of thousands of farmers had defaulted on their loans. During at to the lowest degree one protest, they wore newspaper bags over their heads to hide their faces from creditors.

Neither major party did much to halt the crisis. Perhaps the most prominent vox defending the interests of small farmers was Jesse Jackson, who ran for president in 1984 and over again in 1988, when he won 11 states in the Democratic primary. His success shocked the party establishment. With Martin Luther King Jr'southward Poor People's Campaign equally direct inspiration, Jackson tried to build a broad-based movement that emphasized the specific obstacles facing Black Americans, while drawing in struggling farmers under the banner of shared economical interest.

At a 1985 rally in rural Missouri, Jackson gathered angry white farmers, Black supporters from Kansas City, and matrimony locals to attempt to stop the foreclosure and auction of an 120-acre family subcontract. "This is a rainbow coalition for economic justice," Jackson told the crowd. In the end, the subcontract sold, Jackson lost the primaries, and Ronald Reagan vetoed a relief package for farmers, though he would ultimately sign a farm neb that included aid money.

In Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economic system in the History of the US Working Class, Mike Davis connects the "consolidation of local citadels of capitalist ability on a state or municipal basis" in this period to Reagan'south rising. In the 1970s, voter participation plummeted abruptly, a pattern that mostly broke down forth class lines. The lowest-income earners were substantially more likely to be non-voters, which holds true today, according to Pew Research Center.

Meanwhile, middle and upper strata earners became, if annihilation, more politically involved, throwing themselves into single-issue campaigns like bussing and abortion, and financing the emergence of business organization Pacs. Put another mode, as economical forces bankrupt downward rural communities, those left behind became less inclined to participate in a arrangement that did not help them. Those who benefited, naturally, continued to find electoral politics worthwhile. Members of the gentry became the so-called "median voters" and frequent donors, shaping a system that enriched them while punishing their neighbors.

The next major Democratic effort to take on consolidation in rural America would not come up for another two decades. It can be difficult to remember at present, but during his first campaign, Barack Obama combined talk of hope and change with precipitous criticisms of monopoly and merchandise deals like Nafta. Democrats hadn't talked like this since before the Clinton assistants. He promised to "strengthen anti-monopoly laws" and fight market consolidation in agriculture industries, and the political payoff was substantial. Not only did Obama sweep the Rust Belt, but he also took Iowa and North Carolina. He lost Missouri past a mere 0.13 percent points – a margin unthinkable for a Democrat today.

It'southward easy to see why Obama's anti-monopoly message caught on. To have one example, past 2010, a few big corporations like Tyson and Perdue controlled more than xc% of the poultry industry. Nominally independent farmers were bailiwick to the whims of the large chicken packers, who offered barebones contracts that locked in low prices, required farmers to constantly buy new technology, and denied them the right to negotiate with other buyers. Frequently, farmers didn't even ain the chickens they raised. All of this remains true today.

Obama'south administration tried to foreclose similar consolidation in beefiness production. The industry was trending the wrong way, with a few large corporate meatpackers steadily expanding their hold on hundreds of thousands of small, independent cattle producers. In that location was a sense of hope that here, finally, was an administration that would take on the industry, according to Bill Bullard, whom I caught on the telephone in between service expressionless zones every bit he drove beyond Montana.

Bullard used to operate a cow-dogie operation in South Dakota and today runs R-Calf Us, the largest advocacy group representing contained ranchers and slaughterhouses. Obama's Department of Agronomics held public meetings across the country to hear from ranchers and farmers. Bullard recalled one event in 2011 in Fort Collins, Colorado, for which he estimated that more 2,500 people showed up, with the oversupply spilling out of the event heart.

Nether Obama, the USDA proposed rules that would protect farmers who spoke out against unfair contracts and tried to negotiate amend prices for their products, also every bit stronger enforcement of the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921, a pecker that cracked down on Gilded Age meat monopolies.

This would have been the superlative of Obama'due south agricultural reform, giving the USDA real teeth in preventing mergers and property corporations accountable for anti-competitive behavior. Just piddling came of the effort. Manufacture groups like the National Cattlemen's Beef Association ratcheted up lobbying pressure, and Congress repeatedly blocked stronger USDA corporate enforcement – often led past rural state Republicans. In the terminate, Bullard said, Obama "left the farmers and ranchers out to dry".

Today, the "Big Four" – Tyson, Cargill, National Beefiness, and JBS – control an estimated 85% of the beef industry. Equally R-Calf alleges in an ongoing lawsuit, the companies have illegally colluded to fix artificially low prices, driving independent producers to bankruptcy fifty-fifty as beef prices soared. "We took a private activity," Bullard said, "because we couldn't rely on the Congress or the administration."

In Obama'south last yr in part, Congress finally passed legislation strengthening the USDA's antitrust powers. Then Donald Trump took office. Allies of corporate agronomics were put in charge of the USDA, which promptly threw out a rule that made it easier for minor farmers to sue large meatpackers and demoted the agency'south contained antitrust role to a subdivision of the Agronomical Marketing Service. (Joe Biden is proposing to revive some of the Obama-era rules.)

These bug of corporate domination and consolidation persist, affecting every facet of rural America, while both parties take stood past. Their efforts eased past weak antitrust enforcement, corporate retailers like Walmart muscled out independent businesses in modest towns. Now, dollar stores proliferate in rural communities, sometimes forcing the big box stores to close. There are more dollar stores in the US than Walmarts and McDonald's locations. In many big geographic areas with low populations, people live with reasonable admission to simply one hospital, or even a single healthcare provider. Lack of competition in rural areas is a crucial reason why Obamacare exchanges have failed to go along down healthcare costs, every bit the Intercept reported. And that was before the pandemic, which has caused a record number of rural hospitals to close downward for proficient.

Information technology's no coincidence that this trend toward consolidation tracks a sustained stretch of economic stagnation in the rural Usa. Xl years ago, just over 20% of new businesses came from outside metro areas. By the 2010s, that number had declined to 12%. According to one recent report, 97% of net job growth betwixt 2001 and 2022 went to cities.

And it'south a plain fact that rural areas never recovered from the Bang-up Recession. From 2010 to 2014, counties with fewer than 100,000 people had a 0% net rate of new business creation. While many cities bounced back, jobs and businesses didn't render to rural areas, especially those with predominantly communities of color. Unemployment levels were withal trailing pre-recession levels when the Covid-xix economical fallout arrived to hammer rural areas nonetheless again. Deindustrialized towns keep to bleed population and jobs. Broadband access lags, preventing established industries from keeping upwards and new ones from breaking footing, while gaps in secondary educational attainment between rural and metro areas yawn wide.

At the same time, the rural gentry has but expanded its wealth. According to a central Kansas dairy farmer I chosen, just a few families ain most of the farmland that surrounds his town, with holdings that great to tens of thousands of acres. These families, he said, get the sweetest federal contracts, call the shots on Covid protocols in the church, and tend to rotate in and out of local positions of power in government.

This isn't limited to Kansas. Using county data from 1980-2016, a 2022 peer-reviewed written report published in Population Research and Policy Review found an clan between the chronic population turn down in rural areas and an increment in income inequality. In other words, the economic forces that take meant immiseration and population pass up for rural economies have benefited a small-scale class of capitalists. This relationship, write the study's authors, "suggests that income and other forms of wealth (by extension) are becoming increasingly concentrated into the hands of a select few".

A fter Donald Trump's election in 2016, these compounding rural crises became something of a preoccupation for national media and mainstream liberals. Rural America suddenly seemed to them a afar shore, domicile to strange customs, backward people, and jokes that weren't funny. National reporters dropped in to diners and filed dispatches from Trump rallies. Pundits wrote countless columns with titles like "Why rural America voted for Trump", "Penthouse populist: why the rural poor love Donald Trump", and "Explaining the urban-rural political divide".

Autonomous politicians such as Tester and the onetime Missouri senator Claire McCaskill criticized the party for abandoning moderates and recommended that it run candidates who could relate to rural voters – there'due south a throughline between these suggestions and the cowboy hats.

Trump'south success in rural areas and among non-higher-educated whites spawned a market for books that sought to explain not-coastal areas. The condescending infatuation with JD Vance's Hillbilly Elegy was the well-nigh obvious example, but more than sophisticated works – including Arlie Russell Hochschild'southward Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Correct, Nancy Isenberg's White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, and Elizabeth Catte'southward What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia – also became prominent.

Four years afterward, though Trump didn't win, he took an even greater share of the rural vote. In 2020, he won roughly xc% of rural counties. Whatsoever lessons Democratic strategists have absorbed do not seem to exist working.

T hither'southward a sure sort of liberal who looks at all this and writes off rural areas as deserving of any policies the GOP inflicts on them. As a New York mag headline blared after the 2022 election, "No sympathy for the hillbilly". For a more recent example, consider this (since-deleted) tweet from Nell Scovell, a television writer who co-wrote Lean In with Facebook's Sheryl Sandberg, in response to the tornadoes in Kentucky that killed more than lxx people in December:

Sad Kentucky. Maybe if your 2 senators hadn't spent decades blocking climate legislation to reduce climate change, y'all wouldn't exist suffering from climate disasters. If it'southward any consolation, McConnell and Rand have f'ed over all of usa, too.

This sentiment reared its head online after the West Virginia senator Joe Manchin blocked the Biden assistants'due south Build Back Ameliorate Act. Trading in some of the nigh reprehensible stereotypes about Appalachia, the actor Bette Midler wrote on Twitter:

What #JoeManchin, who represents a population smaller than Brooklyn, has done to the rest of America, who wants to motility forward, not backward, like his state, is horrible. He sold united states out. He wants us all to be just like his country, Westward Virginia. Poor, illiterate and strung out.

Lazy thinking of this sort is what happens when y'all don't brand form distinctions. The existence of the rural gentry class – and increasing income inequality that coincided with economic decline in rural areas – ought to make articulate that not all rural Americans are voting against their class interests when they side with Republicans.

The wealthy voted for Trump, and Trump rewarded them with tax cuts. But rural political conservatism relates to rural economical conditions in other, more complicated ways. During the Peachy Recession, Katherine Cramer, a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, spent several years conducting ethnographic studies on rural, often white, Wisconsinites. She found a persistent sense that rural areas and the people who live there are mistreated, creating a recognizable "rural consciousness". People felt non only that they had been abandoned by the regime, merely that cities and cultural elites hoarded power and prestige at the expense of rural areas.

Some of the rural discontent is unquestionably racial. The GOP appeals to people who want to preserve the social and economic benefits that whiteness confers, or to restore the loss of privileges brought by an increasingly diverse populace. A recent assay of 2022 voting patterns by the University of Virginia'due south Centre for Politics establish that among not-college educated white voters, "racial resentment" was i of the highest predictors of bourgeois political views.

Simply all this applies to enough of suburban Trump voters, too. To the extent that a rural consciousness exists, it's entangled with a sense of having lost something while the residual of the country moves ahead. This, Cramer plant, creates a persistent "us v them" view of the world. In Wisconsin, this rivalry manifests as anger at cities – where, it should exist said, almost of the country'south non-white population lives – but also at white-neckband professionals and public employees of all kinds. These attitudes can also be establish in western Colorado, with the frustration directed at the Denver and Boulder population centers. Western Slope economies depend on tourist dollars from these metro areas, nonetheless at that place'south a potent sense of resentment toward the cultural and economic power concentrated on the other side of the Rockies.

I encountered this sentiment in the fall of 2020, when I interviewed an unaffiliated, starting time-fourth dimension candidate for local office named Trudy Vader. Vader'due south family had been forced to sell their ranch during the farm crunch of the 1980s. Today, what's left of the ranch holds a mobile home, a horse pen, and petty else. A few wealthy families ain most of the county'due south private ranchland. The property's sale was ane of her formative experiences. Her sense of having one time held and now lost something dear could not exist separated from other, less concrete losses: her ranching boondocks overrun with tourists during the summer, agronomics's decline as a cultural force, a hunch that people worked harder dorsum in the solar day.

Vader's default conservatism – her nostalgia for an era that might not have been every bit great as she remembers – makes some sense in this context. But she remains a landowner, a status that millions of Americans cannot hope to achieve. If economic change can help create distinct rural identities, those identities can as well become relatively uncoupled from material realities, spiraling out in unpredictable ways that may not easily trace back to economic weather condition.

In his book The Reactionary Listen, Corey Robin summarizes the mindset of conservatives similar Vader:

People who aren't conservative oftentimes fail to realize this, just conservatism really does speak to and for people who accept lost something. It may be a landed estate or the privileges of white skin, the unquestioned potency of a husband or the untrammeled rights of a factory owner. The loss may be as textile as money or as ethereal every bit a sense of standing. It may be a loss of something that was never legitimately endemic in the first place; it may, when compared with what the conservative retains, be small. Even so, information technology is a loss, and zippo is ever so cherished as that which nosotros no longer possess.

The conservative mindset that Robin describes is widespread, but information technology is non absolute, even on an individual level. Vader's primary issue during the race, one that she stressed throughout the entrada, was a local affordable housing crisis, which she supported radical measures to address. (Politics may be national, but major party categories are still scrambled at the local level.)

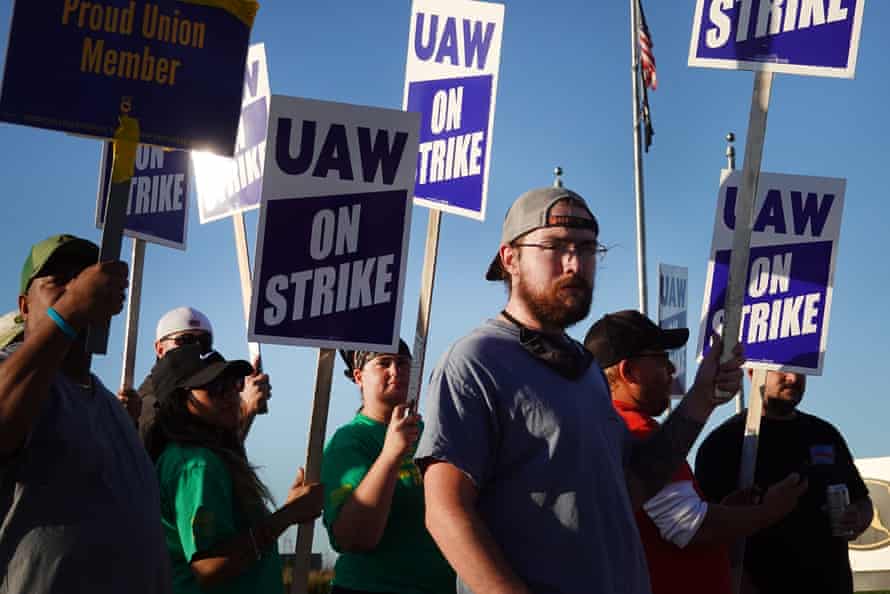

There'southward evidence that the political makeup of rural America is neither as simplistic, nor every bit homogenous, every bit either major party's treatment of information technology would lead the states to believe. The past six months accept seen one of the most sustained periods of labor activeness in decades. More than a dozen strikes and unionization efforts are happening around the land correct now, many of them in small towns and midsize industrial cities in rural areas. Every solar day, reports appear of workers walking off jobs that demand too much for too piddling pay.

For months this by fall, John Deere workers stood on picket lines in towns in Iowa, Illinois, and Kansas, and came away with pay increases and a strong bargaining understanding.

In late 2021, later strikes across the midwest and rust chugalug that lasted more than than 2 months, Kellogg workers won an agreement that removed a 2-tier benefit system and ensured no factory closures until 2026.

In Topeka, Kansas, last summer, several hundred Frito-Lay workers stopped working, alleging low pay, long hours, and unsafe conditions.

Since April, Alabama coal miners have been hit – in November, hundreds protested outside the New York City headquarters of the financial giant BlackRock, the largest shareholder in the mining corporation they work for.

In early November, simultaneous strikes in hospital maintenance and steelwork meant that iii% of the entire town of Huntington, West Virginia, had walked off the job. Concluding year's strike wave was preceded in 2022 by gigantic instructor strikes that began in Due west Virginia and spread to ten other states.

And in response, the Autonomous party has washed cipher, as far as I can tell. Whether it's a strategic lapse or an indication of the special interests Autonomous politicians are beholden to is unclear. Either way, there's no increased urgency to pass the Pro Act, no organized attempt to assist workers, to tap into this energy, to show which side they are on.

At a broader level, it'south more evidence that Democrats neglect the internal course structure of rural America at their own peril. The rural gentry has real stakes in the status quo.

In that location are also, if you set bated received stereotypes and pay attention, people working to alter the way things are today. The inhabitants of rural America are as complex and diverse as people anywhere, and no less of import. Forget the balloter map. At that place is opportunity here for people who are up for doing the work of politics: meeting people where they are, finding common interests, building institutional strength, and trying to persuade others to join in, while being guided by local bug and concerns.

When change occurs, this is how it happens. And equally for Democrats who recollect that this piece of work isn't worth it, or that rural America is somehow unworthy of their efforts, well, the joke is nonetheless on them.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/feb/22/us-politics-rural-america

0 Response to "Update After the Election We Chatted With Cramer Again About Rural Whites Trump and Racism"

Post a Comment